By Peter Petrov

They say that the spontaneous affinity for Latin music runs in the blood, and when you take a closer look at all the history, cultural and social heritage, and interconnected human faiths that give Latin rhythms and harmonies their distinctive flavor and spice, this saying starts to feel more like a historian’s observation than a myth.

European and Arab Influences

Before the arrival of Columbus at the Americas, the Mayans, Aztecs, and Incas who inhabited the lands now known as Central and South America, expressed themselves musically largely through percussion and wind instruments, especially flutes. These ancient traditions still remain palpable in traditional Latin music like Andean music, for example.

With the start of the New World and the colonization period, the Spanish and Portuguese brought their languages, cultures, traditions, and music. The Spanish, in particular, carried a rich musical mix of European and Arab influences as their culture was tightly entwined with the one of the Moors, who were Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Along with their feel for music, the Spanish also introduced their instruments like the guitar and the guiro, the latter in particular now a signature feature of certain Latin musical genres today like son, trova, salsa, plena, and the traditional Panamanian and Colombian music called típico.

African Influences

The Spanish and Portuguese didn’t just bring their own musical culture to the New World, but also the one of their African slaves. The African music they brought with them became perhaps the single most recognizable element of Latin music.

Drumming was the very pulse of religious ceremonies in Africa, imbued with the spirit of these lands and their inhabitants. During the slave trade era, drumming served as a form of communication, a way to send codes over long distances. Drumming was among the few rights that fortunately wasn’t taken away from the African people in the New World. As such, it became a backdrop for free-form dancing and grew into perhaps their purest source of joy.

At busy ports all over the Americas and the Caribbean, slaves and natives mingled and exchanged their unique takes on different rhythms, dances, and songs, giving birth to spontaneous musical collisions that could never be replicated in the very same way elsewhere.

The African musical influence is considered most dominant in widely popular Latin genres like samba, salsa, merengue, bachata, and timba.

Birth of Modern Genres

Salsa

Salsa uses percussion instruments like the clave, maracas, conga, bongo, tambora, bato, and cowbell to recreate the back-and-forth dynamic of traditional African songs in which drumming is a blend of music and communication.

The exact origin of salsa is debated, with some claiming it’s the continuation of Afro-Cuban music, and as such comes from Cuba, whereas others trace its beginnings back to 1960s New York where many Cuban and Puerto Rican musicians developed it.

Some salsa musicians even view the style as more of a personal interpretation and vision rather than a fixed genre. This outlook is perhaps best captured by the words of Tito Puente, a famous percussionist and bandleader who’s considered to be one of the founding figures of salsa: “I’m a musician, not a cook.”

Rumba

With a name that means “party,” rumba is a vibrant form of music and dance that dates back to mid-19th century Havana. Again, the spirit of the African slaves and their drumming pulses through the rumba rhythms, which is accompanied by the melodies of Spanish colonizers.

The original form of rumba was the spontaneous outpouring of Cuban hot blood that never stopped simmering even under slavery’s cold embrace. Slavery ended in 1886, but rumba lived on and for a while kept being suppressed because of its “primal” nature in the eyes of rulers. In 1925, President Gerardo Machado basically banned it by making “bodily contortions” and drums of “African nature” illegal in public, but later, Fidel Castro embraced it as the Afro-Latin music of the working class.

It’s worth mentioning that the ballroom-style rumba that is internationally popular today is vastly different from its ancestor, and many believe the beats of the original rumba can be truly felt only when drummed on stools and domino tables on the streets of Havana.

Samba

It’s funny to think that what is now one of the vibrant symbols of Brazil and its cultural diversity was once the subject of rebuke and contempt by the upper-class citizens and European settlers who saw it as obscene.

Samba was born in the region of Bahia, or “Little Africa,” where it was performed to honor the Gods in the traditions of Angola, where most African slaves in Bahia came from. In fact, the word “samba” is considered to have a dual origin – from the Angolan “semba,” meaning “naval bump,” and from “kusamba,” samba being the infinitive form, which in Brazil signifies “to pray.”

When slavery was abolished in 1888, former slaves from Bahia migrated to Rio, marking the beginning of samba’s contemporary history. For a while, it was viewed as an entertainment for the lower classes who would gather around in the favelas (Latin American ghettos) and dance together in what they called “blocos” – dance groups.

A turning point in the public perception is considered to be Ernesto Dos Santos’s “Pelo Telefone” in 1917, which officially started Samba Carnavalesco. From there, samba schools spread through the country and even to Europe, turning samba into a movement and a source of national pride.

Today, samba has come to epitomize international harmony and vigor.

Merengue and Bachata

Merengue and bachata are by far the two most iconic genres that came from the Dominican Republic, and similar to other types of Latin music, they are the products of the diverse influences Spanish settlers brought to the island through the African slave trade.

Despite both dissolute genres, traced back to brothels and low-class bars in the 19th century, dictator Rafael Trujillo was bothered only by bachata’s roots and branded it the lower art form. He imposed merengue as the national music, especially between the 1930s and 1960s, while bachata was enjoyed only in the countryside.

It wasn’t until Trujillo’s fall that bachata was officially labeled a music genre in the 1960s. It grew to be perhaps even bigger than merengue, both within the Dominican Republic and around the world.

Reggaeton

Reggaeton is the youngest of Latin music genres, but that doesn’t make the tropical cocktail of its musical influences any less rich, with its flavors of Jamaican reggae rhythms, merengue, bomba and plena (Puerto Rican percussion-heavy music styles and dances with African roots, originally performed spontaneously on the streets) and sometimes salsa.

There’s a reasonable debate whether reggaeton originated in Panama or Puerto Rico. On the one hand, the Panama Canal is credited as the place where Jamaican music finally collided with Latin rhythms and dances, as in the early 20th century a lot of Jamaicans migrated to work there; on the other, some of the most influential and earliest purveyors of this music come from Puerto Rico, and today, the Caribbean island instantly evokes this deeply percussive music and the signature panache of its performers.

Either way, reggaeton is yet another example of the fascinating intersections of various musical styles that spontaneously occur in those latitudes.

It’s no wonder Latin music holds such an allure over the whole world. Hardly any other musical niche is as replete with history, distinctive flavor, rhythms and harmonies, and most of all, stories of cultural and social segregation, which eventually turn into stories of cultural and social integration.

Similar Posts

Famous Artists from Key West: The Creatives Who Shaped the Conch Republic

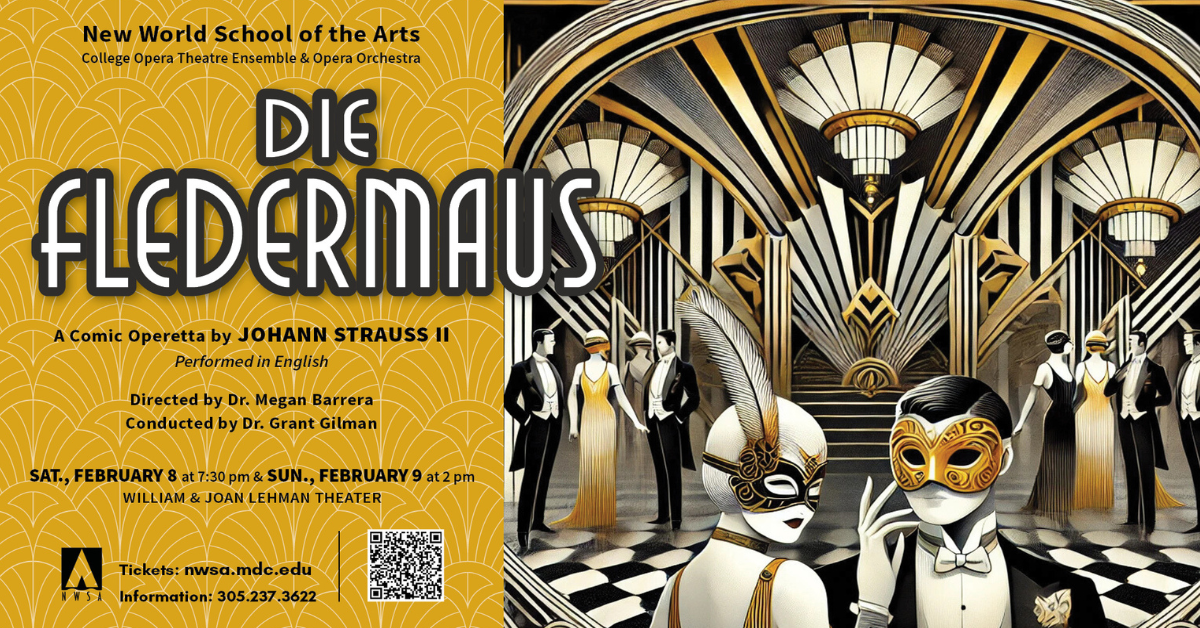

OPERA THEATRE ENSEMBLE PRESENTS DIE FLEDERMAUS WITH A CHARMING ROARING 20’S FLAIR

Recent Posts

Savoring Every Mouth-Watering Minute of SOBEWFF

The South Florida Theatre League Announces the Recipients of the 2025 Remy Awards

Coral Gables: Your Guide to Art, Culture, and Outdoor Attractions