Certain art pieces are imbued with so much history, culture, emotion, and life that even the most exact replica couldn’t pin down their exact essence. For the casual observer, this might be irrelevant, and therefore a search for their original source – pointless. But for many true art lovers, like myself, experiencing an original in person is like looking at the world from the same, unique vantage point from which the artist once saw something nobody else could.

It’s an intimate experience like none other, an almost surreal synchronization of your energy combined with the artist’s in a perfect moment in time.

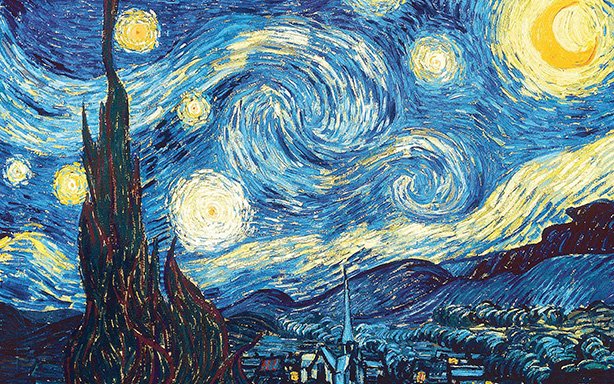

10. The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh

The Starry Night hardly needs an introduction, but here’s ours anyway: Vincent Van Gogh’s most signature masterpiece and an international symbol of art; a beautiful island of serenity, floating amidst a sea of torment inside a mad genius’ mind. It actually depicts Van Gogh’s view from the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum near Saint-Remy-de-Provence where the artist checked himself in after suffering a mental breakdown and famously cutting off his own ear. The artist left out the bars and focused on the night’s vibrant beauty, which he seems to have always felt a special affinity for. His ability to portray luminance is characteristic of the impressionism artistic movement and is what gives the painting its distinctive glow, like it’s actually pulsing with light.

As if the story behind the painting wasn’t enough to envelop its beauty with a mystic layer, the big cypress tree in the foreground that rises to the night skies is by far not coincidental. Those trees are generally associated with death and cemeteries, and what Van Gogh once said about stars puts everything into an eerie perspective: “Looking at the stars always makes me dream. Why, I ask myself, shouldn't the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? Just as we take the train to get to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to reach a star.”

All this makes The Starry Night at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Manhattan something to behold.

9. The Water Lily Pond by Claude Monet

During the last thirty years of his life, impressionist Claude Monet drew inspiration from the landscape around his property in Giverny, especially his water gardens, giving birth to the famous Water Lilies paintings. Among those was a smaller series, centered around the wooden Japanese footbridge and the pond beneath, which we can admire in The Water Lily Pond. It’s a vertical view of different pieces of nature and their reflections in the pond that seamlessly blend into a warm-colored idyll. The painting can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

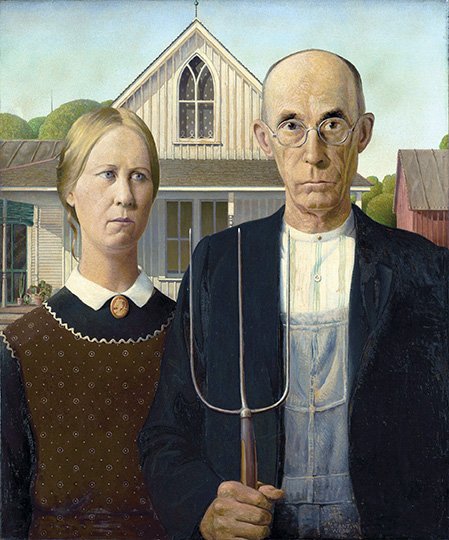

8. American Gothic by Grant Wood

American Gothic is a fascinating and controversial tribute to midwestern culture and character. Its details, austereness, and of course, the eerily stretched out faces are haunting and convey a mix of ideas. The painting is based on a house Wood saw while visiting the small town of Eldon in his native Iowa. At first glance, the painting certainly doesn’t invoke the most pleasant feelings. The figures look devoid of even the faintest traces of emotion and romanticism. However, within the context of 1930s America, Wood aimed to depict the stern, unadorned toughness, necessary to survive the transition from the simplicity of farm life to the industrial era. American Gothic hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago.

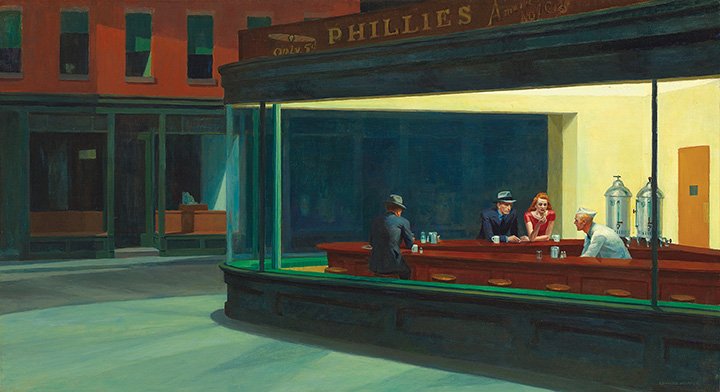

7. Nighthawks by Edward Hopper

Another one at the Art Institute of Chicago, Nighthawks is based on “a restaurant on New York’s Greenwich Avenue where two streets meet” from the 20th century, but the painting breathes such a palpable air of loneliness that it can engulf viewers from any time or place. It is somewhat reminiscent of a noir graphic novel, but rather than an interplay between shadows, the focus is on the fluorescent lights which are one of the trademarks of the 1940s and its late-night diners. Hopper brings us close enough to the scene to let us fully grasp its simplistic beauty, yet still keeps us far enough to obscure any distinctive features of his figures, making their loneliness even more universally relatable and emphasizing the isolation of the diner from the outside world. Even though the diner is filled with melancholy, it also emits a sense of comfort, as if its doors are always open for those who wander in the night.

6. Children on the Seashore by Joaquin Sorolla

Children on the Seashore is a painting created in 1903 by Valencian artist Joaquin Sorolla who is most famous for capturing Spain's Mediterranean charm and spirit in idyllic landscapes filled with figures, relishing nature and life. The piece possesses all of its creator's trademarks – frivolous children playing on the beach, bathed in warm sunlight and illuminated by its bright reflections on the water’s surface. Children on the Seashore is on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

5. The Birth of the World by Joan Miro

Portraying something as profound the birth of the world is probably the most ambitious endeavor an artist can undertake. Miro has used a blended approach to recreating not a specific scenario but rather the idea of genesis. The artist first applied paint through different motions on an unevenly primed canvas, which gives the painting its chaotic, random feel. Miro describes this part as somewhat of a flow state: “Rather than setting out to paint something I began painting and as I paint the picture begins to assert itself, or suggest itself under my brush.… The first stage is free, unconscious.”

However, he then chose to add these specific lines and shapes after reading different studies. This way, the painting conjures up images of a random force of nature, a raw and intangible energy starting to take up different, more specific forms. The Birth of the World is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

4. Ginevra de’ Benci by Leonardo da Vinci

This portrait is the only Leonardo da Vinci painting on public display throughout all the Americas. It depicts a somewhat classic-looking for the time face, but perhaps a tone or two more somber. The juniper bush around the girl’s head resembles a hallo and alludes to her chastity. The Latin motto “beauty adorns virtue” can be found on the back of the painting, which perhaps refers to the tight connection between beauty and virtue at the time. The painting hangs at the National Gallery of Art.

3. Luncheon of the Boating Party by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

This vibrant painting represents the somewhat revolutionary concept for the 19th century, of people from different social classes sharing a casual, fun party. This reflects the arising changes in Parisian society. Renoir has masterfully managed to imbue the scene with spontaneity, life, and dynamics even though he spent months painting it and making different changes and touch-ups. This painting can be found at The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. and remains its most popular painting to date.

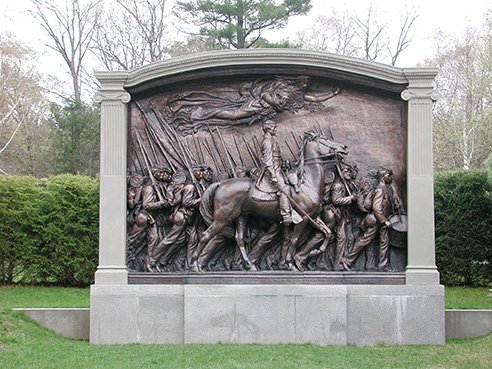

2. Shaw Memorial by Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Shaw Memorial is one of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ most monumental sculptures. It’s a captivating tribute to one of the first official units of black soldiers during the Civil War. The idea for Shaw on the horseback at the very center was borrowed partly from Napoleon’s depiction in the painting Campagne de France 1814 the sculptor saw in France. What makes this sculpture so historically important is how “The faces of the men are so individualistic, so human at a time when African Americans were reduced to stereotypes,” says Lonnie Bunch, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The sculpture captures the forward, proud motion of men of different expressions, ages, and characters, united by a common goal above anything else. It’s on view at the National Gallery of Art.

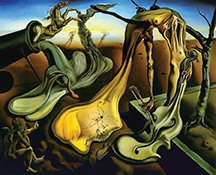

1. Daddy Longlegs of the Evening-Hope! By Salvador Dali

Salvador Dali was highly extravagant both as an artist and as a person, but there was one particular peculiarity, too controversial even for his fellow surrealists’ open minds to accommodate – his fascination with Hitler. It ultimately got him exiled to North America between 1940 and 1948, and Daddy Longlegs of the Evening-Hope! is Dali’s first painting from this period.

Therefore, it can be speculated (since nobody could say anything with certainty about Dali’s work) that the entire painting is filled with apocalyptic metaphors of the horrors of World War II. The melting, soft “head” of the female body being eaten by ants symbolizes Europe’s demise. The violoncello and bow next to it, also melting away, might also be another representation of the rotting European culture under the fascist regime, while the two inkwells next to the female body’s breast stand for the signing of a treaty. Either way, as intriguing as attempting to decipher the painting’s various elements and nuances might be, the work of Dali and other surrealists is often best enjoyed as if you’re in a dream, which is what you can do at the Salvador Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Surely you can see a replica of any of those pieces and still get a good sense of their beauty and meaning. But are you willing to forego the experience of viewing them as they were intended, missing the countless tiny details you might discover in their presence? Would a replica move you in the same way the original will? Only you can say for yourself.

Similar Posts

City of Miami Beach to Launch Free Water Taxi Service and Dedicated Shuttles for Art Week Miami Beach

Top Dining and Drinking Spots During Miami Art Week 2024

10 years of Art of Black Miami

How Do You Want to Look at Art?

Recent Posts

The Last Christmas Review

The Florida Renaissance Festival Brings Patrons Back in Time Again at Quiet Waters Park for its 33rd Anniversary

The Ultimate Guide to Navigating Art Week 2024 Like a Pro